Looking at Canada’s COVID-19 experience through a well-being lens

Since mid-March 2020, Canada has faced profound economic and social impacts as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. For obvious reasons, much attention has been placed on the immediate health effects of the pandemic and the state of the economy. However, many other aspects of the quality of life, or well-being, of Canadians have also received significant attention. For example, data reflecting the multiple dimensions of well-being were prominently featured in the Economic and Fiscal Snapshot 2020.1 Along with economic and labour market trends, the federal government highlighted the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across education and skills development, gender-based violence and access to justice, poverty, health and well-being, and gender equality dimensions, emphasizing the diversity of impacts.

Prior to the spread of COVID-19, the Government of Canada expressed interest in further exploring well-being measurement and its use as a policy tool.2 In December 2019, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau mandated the Minister of Middle Class Prosperity and Associate Minister of Finance “to better incorporate quality of life measurements into government decision-making and budgeting, drawing on lessons from other jurisdictions such as New Zealand and Scotland.”3

Given the scope and the diversity of the reports and studies that examined the impacts of the pandemic on well-being, it can be challenging to absorb and understand all the ways in which quality of life has been affected by COVID-19. The well-being literature offers an approach that may help.

Examined through a well-being lens, quality of life is recognized as multifaceted and multidimensional. A holistic understanding of well-being comes from looking at both the economic system and the diverse experiences and living environments of people. The multiple facets of well-being can be represented as connected domains in a comprehensive well-being framework; in turn, indicators can be proposed to represent and track changes in the chosen domains. Some dimensions of well-being may improve over time, while others may deteriorate. Outcomes for some dimensions may be observed to affect the population in similar ways, while outcomes for other dimensions will have more varied impacts, with some groups experiencing significantly lower well-being than others.

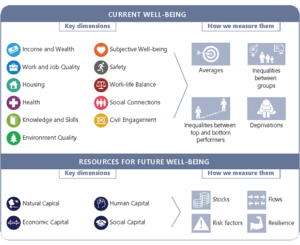

This report brings together diverse findings that illuminate changes in quality of life since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and provides valuable insights through examining these results through a well-being lens. Several widely used frameworks exist to describe the dimensions of well-being, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Framework for Measuring Well-Being and Progress (Box 1). As with other well-being frameworks, the OECD model divides well-being into interrelated economic, social and environmental dimensions, and underscores that both levels and inequalities in these domains influence the well-being of a society.4 As suggested in the Prime Minister’s 2019 mandate letter mentioned above, governments worldwide have been developing their own well-being frameworks and systems of indicators to incorporate additional measures that are important to citizens. For example, Scotland, New Zealand, Iceland and Wales have each moved to create “well-being economies” to help direct their national spending.5

The OECD Better Life Initiative

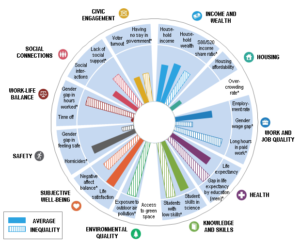

As well-being is multifaceted, a well-being framework can provide a useful guide to understanding quality of life across populations. While there are several frameworks available, the OECD Framework for Measuring Well-Being and Progress, created to address a key priority that the OECD is pursuing as part of the Better Life Initiative, provides a starting point for Canada. The framework was built upon on national and international initiatives, academic literature, expert advice and input from National Statistical Office represented on the OECD Committee on Statistics and Statistical Policy. In the framework, current well-being includes 11 dimensions, covering outcomes at the individual, household and community levels. It also includes four resources for future well-being: natural capital, economic capital, human capital and social capital. 6

The OECD well-being framework is used to derive the OECD Better Life Index, which allows for a comparison of well-being across countries using a set of specific indicators for each of the 11 well-being dimensions. The OECD uses these indicators to undertake analysis for the series How’s Life?, which evaluates quality of life in 37 OECD member countries and four partner countries every two years. The How’s Life? 2020 edition focused on data for over 80 indicators, including 24 headline indicators, using 2018 data or data for the latest available year.7 Recognizing that the well-being of a society is reflected both by the “level” of its outcomes as well as by the inequalities in the distribution of these outcomes, the indicators in the framework reflect both absolute and relative perspectives.

This paper describes how selected aspects of well-being have been affected during the COVID-19 pandemic period (at least until the date of this publication release) focusing on the following areas, which have been drawn from the OECD framework:

- Income and wealth: What do the data say about the current financial challenges faced by Canadians?

- Knowledge and skills: What are some of the experiences associated with accessing education, particularly with the move to increased online education?

- Work–life balance: How are families in Canada faring, especially with respect to managing work and child care responsibilities?

- Health: What have been the impacts of the pandemic on mental health, and how have these outcomes highlighted diversity of experience?

- Environment: How are Canadians turning to their local environments and parks as restrictions to mobility are in place?

While other questions could, of course, be studied, those above were chosen because they represent a variety of domains as well as areas where there have been recent data collections in Canada. Future research could delve more deeply into the domains explored here or extend to the several other domains not covered.

This paper concludes by reflecting on the importance of the connections – within and between work, family, technology and the environment – as a source of resilience during the pandemic. While the sampling of variables in this paper is intended to provide a demonstration of the strengths and vulnerabilities of individuals and families in Canada in a coronavirus-impacted world, it also illuminates the importance of connections between these individuals and their families and the social, economic and natural capital available to them in this period of pandemic.

Income and wealth: Family financial well-being has been challenged but has also been supported by changes in household habits and pandemic relief programs

The pandemic-induced partial or full closure of many business and workplaces in March 2020 devastated the labour force and threatened to wreak havoc on the financial security and stability of Canadian individuals and families. By April 2020, 5.5 million workers had been negatively affected by the COVID-19 economic shutdown in the form of lost employment or reduced hours, a number that was still as high as 1.1 million by December 2020.8 Since economic shutdowns/slowdowns often impact people already living with low incomes more than those in higher income situations, it is not surprising that nearly 5 in 10 (46%) people in Canada with incomes under $40,000 said their income had worsened between the onset of the pandemic and October 2020,9 compared with 3 in 10 (27%) of those with incomes over $40,000.

Since April 2020, Statistics Canada has included a question related to financial well-being in its monthly Labour Force Survey: “In the past month, how difficult or easy was it for your household to meet its financial needs in terms of transportation, housing, food, clothing and other necessary expenses?” The resulting indicator reflects the evolution of perceived financial security, with financial resilience little changed over the pandemic period (Figure 1). As of February 2021, around one-fifth (20.4%) of Canadians reported difficulty in paying expenses related to housing, food, transportation, clothing and other necessary expenses.

A significant share of those who had lost work hours or who had become unemployed struggled to meet the financial needs of their family in the first year of the pandemic. Nearly half (42%) of Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) recipients found it difficult or very difficult to meet necessary expenses in September 202010 and, in October 2020, more than half (53%) of the long-term unemployed, who had been searching for work or on temporary layoff for 27 weeks or more, said they had difficulty paying for necessary expenses. This was almost three times the share of those who were employed or not in the labour force (e.g. not looking for work, retired, a student) who expressed challenges paying their bills (19%).11 Both unemployment and financial stressors have been disproportionately felt by women, youth, Indigenous people and minority groups.12 For example, among those who experienced job loss or reduced work hours, 65% of Indigenous participants in a Statistics Canada survey reported a strong or moderate negative financial impact in June 2020, compared with 56% of non-Indigenous participants.

Throughout the pandemic, many Canadians have expressed fear and anxiety over the pandemic’s potential impact on their financial situation. As with the actual impacts, this fear has not been experienced equally by all Canadians. A survey undertaken by the Vanier Institute of the Family, the Association of Canadian Studies and Leger13 found that, while more than half (53%) of adults aged 18 and older reported in April 2020 that the coronavirus outbreak posed a major threat to their personal financial situation, some were less worried than others. Thirty-six percent (36%) viewed the crisis as only a minor threat and 11% said the pandemic did not pose a threat to their finances. Many of those who reported that they did not feel their financial well-being would be negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic were professionals whose jobs could be transferred from an office space to their home or were persons working in industries less affected by closures.14

Industry, sector and roles impacted people’s sense of financial well-being too: fewer than 15% of people working in management, financial, public services or public administration industries said that they found it difficult or very difficult to meet household financial needs in May 2020.15 In comparison, the share of those working in the food and accommodation industry who had difficulty meeting their financial needs was more than double that, at 33%.

Gender, identity, culture and community also makes a difference on financial well-being. One Statistics Canada COVID-19 study found that 44% of South Asian respondents, 38% of Black respondents and 36% of Filipino respondents reported that the pandemic had had a “moderate” or “major” impact on their ability to meet their financial obligations as of May 2020 compared with 22% of White participants. Groups designated as visible minorities were also more likely to report “fair” or “poor” mental health (28%) or symptoms consistent with moderate or severe generalized anxiety disorder (30%) than White participants (23% and 24%, respectively).

“Additional evidence on Canadians experience with financial hardships during the pandemic period is provided by the Seymour Financial Resilience IndexTM.16 The index measures a consumers’ ability to get through financial hardship, stressors and shocks as a result of unplanned life events, with measurement of consumer financial resilience at the national, provincial, segment and individual household levels. The index highlights that the financial resilience of Canadians at the national level has improved as the pandemic has drawn on, in part thanks to swift and significant financial support from Government and Financial Institutions as well as to changing consumer and financial behaviours, with many people taking steps to stabilize or improve their financial resilience during the course of the pandemic. The index is calculated using nine indicators, including measures of financial stress over current and future financial obligations; peoples’ liquid savings buffer; financial behaviours; a self-reported credit score and the availability of social capital (i.e. a close person who could provide financial support in times of hardship)17 . Using the index, the baseline mean financial resilience score for Canada at the national level in February 2020, just before the major onset of the pandemic in Canada, was 49.58 on a scale of 0 to 100 - revealing that pre-pandemic Canadian households were, at the national level “Financially Vulnerable” to financial hardship, stressors or shocks. As of June 2020 however, the mean financial resilience index score at the national level was 55.58; 54.53 in October 2020 and higher at 55.69 in February 2021, signalling improved financial resilience for individuals and families – although many households are currently being temporarily ‘cushioned’ by financial relief. Furthermore, households which were identified as falling into the “Extremely Vulnerable” segment have been shown to be taking steps to adjust to their situation and bridge through, with 80.7% significantly reducing non-essential expenses, 66.2% drawing down their savings and 43.6% increasing their borrowing to meet everyday expenses as of October 2020.

The Seymour Financial Resilience IndexTM also highlights that more financially vulnerable households are being more negatively impacted by the pandemic causing financial hardship compared to ‘Financially Resilient’ Canadians. Consequently, in October 2020, 64.2% of ‘Financially Vulnerable’ and ‘Extremely Vulnerable’ households completely or somewhat agreed that the pandemic is causing their household significant financial hardship and 71.7% completely or somewhat agree that money worries make them physically ill (compared to 12.5% of ‘Financially Resilient households’, representing 28% of the population). 81.3% of ‘Extremely Vulnerable’ and ‘Financially Vulnerable’ households also completely or somewhat agreed that money worries negatively impact their overall health and well-being, compared to just 12% for ‘Financially Resilient’ households.

In addition to the efforts that Canadians have made within their families to cope with pandemic impacts over the course of the last year, the financial situations of more than 8.9 million individuals have been supported by the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and Employment Insurance (EI).18

According to some experimental weekly family income estimates that Statistics Canada constructed for January to September 2020, pandemic relief benefits such as the CERB and EI may have offset a potential surge in low income between February and April 2020 for a large proportion of Canadian families. Using data reported through the Labour Force Survey, and data from the CERB pandemic relief program, these estimates showed a substantial surge in the proportion of persons living in families with below-Low-Income Measure (LIM) weekly earnings from 26% in February to 38% in April. There was then a steady decline to 24% by September 2020. However, when these figures were recalculated to include pandemic-related benefits (child benefits, GST/HST benefits, Employment Insurance and the CERB), the adjusted share of persons living in families with below-LIM weekly income was 21% for February 2020, 22% for April 2020 and 16% for May through September 2020. Notably, then, the proportion of persons living in families with below-LIM earnings was 16 percentage points lower in April when benefits were included, compared with when benefits were not included, that is, benefits appeared to be helping many Canadians to stay above low-income situations. Similar results have emerged in the United States, whereby poverty declined in the first few months after the start of the pandemic as a result of emergency response measures in that country.19

Knowledge and skills: Technology provides connections to work, school, friends and family, but not all Canadians have equal access

During the pandemic, the Internet has become a critical tool for working and learning at home, maintaining relationships and social connections, booking and attending medical appointments, entertainment, shopping and many other activities. In 2020 and 2021, many Canadians can scarcely imagine easily living and functioning without the Internet.

According to the CRTC,20 no matter where you are, your phone should be able to connect to the Internet, and you should have an Internet connection with access to broadband speeds of at least 50 Mbps download and 10 Mbps upload and access to unlimited data. Although (as of 2019) the vast majority (87.4%) of Canadians now have at least the minimum 50/10 speed,21 there is, unfortunately, a drastic divide between those who live in cities and those who do not, with only 45.6% of rural communities having the minimum suggested speeds. In November 2020, the federal government announced $1.75 billion to help connect Canadians to high-speed Internet across the country. Their goal is to have 98% of Canadians connected by 2026 and 100% by 2030.

The 2018 Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS) found that, in addition to discrepancies between rural and urban populations, there are large differences in access to technology based on socioeconomic status. In fact, in 2018, 4% of households in the lowest 25% of the income distribution lacked Internet access, compared with just 0.2% of households in the highest income bracket. Low-income households were also more likely to have less than one device for each household member (63% vs. 56% of high-income households).22 This has left many of those already at a disadvantage without the resources to learn and acquire new skills from home during COVID-19 isolation.

As schools moved to virtual platforms due to lockdowns continuing into 2021, the importance of Internet access became paramount. Children learning from home during the pandemic are one of the most affected groups in this respect.23 Existing inequities for students in rural and high-poverty schools have been exacerbated by some students’ limited access to the Internet and thus by restricted communication with instructors during virtual classes. Children in rural areas without Internet access and children living in homes with too few devices or connection speeds that cannot sustain multiple users are at risk of falling behind in their education and social development. They are also at risk of lower social well-being because of having fewer online connections.

Even children who have reliable access to technology may have seen impacts on their capacity to learn and their overall well-being as a result of having to acquire learning and skills online during the pandemic.24 For example, in May 2020 the Angus Reid Institute reported that although 75% of youth claimed to be keeping up with school while in isolation, many were also unmotivated (60%) and disliked the arrangement (57%).25 Concerns have also been raised when it comes to reductions in physical fitness and activity levels of young Canadians who are spending more and more time in front of their screens.26

In addition to the importance of technology for children and youth’s schooling during the coronavirus pandemic, many adults also require an Internet connection for skills and learning related to their work, medical or other needs. The Internet is now a common place to turn to for news, information and online support as well as a way to keep in contact with loved ones. During the pandemic, local health authorities have suggested that connecting virtually is one of the keys to practising social distancing, but, for some without connectivity, this leaves them isolated and feeling frustrated and left out.27

Research on social connectedness through technology reveals that the more participants engage with others via the Internet and other media, the more likely they are to engage in strategies to keep busy and to maintain other positive behaviours, such as eating healthy and exercising. While technology cannot replace human contact and touch, it is a way to cope with loneliness and help maintain health and well-being.28 In other words, technology could be considered critical to maintaining positive connections and quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic.29

Work–life balance: Child care has been a challenge for many parents, but early-pandemic evidence showed strengthened child–parent bonds in some families

The balance between work, life and self-care is critical to well-being. Yet, many Canadians, in particular women in the paid labour force who have young children, find it difficult, and sometimes impossible, to effectively achieve work–life balance. Parents surveyed in Statistics Canada’s crowdsourcing survey Parenting During the Pandemic ranked their number one concern in June 2020 as how to balance child care, schooling and work, with 74% reporting feeling very or extremely concerned in this regard.30 This sense of an inability to effectively balance work and home has continued throughout the pandemic, with a March 2021 Environics study revealing that 25% of Canadians say their work–life balance has worsened due to COVID-19, with almost 3 in 10 (29.8%) parents of children under 18 feeling this way.31

Overall, work–life balance and child care challenges tend to affect women more than men, particularly women aged 25 to 54.32

Women’s employment was disproportionately affected at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and, during phases of reopening, many women have returned to work but at reduced hours. Even with the resumption of in-person schooling in September, 70% of mothers reported that they worked less than half their usual hours compared with September 2019.33 At the same time, many women have still taken charge of a large share of family responsibilities with respect to children’s schooling and some have taken on increased household responsibilities as well, including those who have remained in full-time employment during the pandemic.34

Women have traditionally borne greater responsibility for child care and other domestic duties than men and these responsibilities may be exacerbated by the current environment, particularly with school closures and reduced availability of social services, such as child care and eldercare.35 On the other hand, with many people transitioning to working at home, men now have more potential to be taking on more family care responsibilities.36

Clearly, child care posed a particular challenge for many working parents in 2020. In June 2020, about one-third (33.7%) of participants in Statistics Canada’s crowdsourcing survey said that their children would return to child care once those services reopened: nearly 9 in 10 (88%) of these parents said that child care was necessary if they were to be able to work.37 Nevertheless, more than one-third (36%) of parents or guardians who had one or more children aged 5 or younger needing child care said that they were having difficulty finding an early learning and child care arrangement. Of those who reported difficulties finding suitable child care, nearly 5 in 10 (48%) reported affordability as a reason, almost 4 in 10 (38%) cited challenges in finding care that fit their work or school schedule and close to 4 in 10 (37%) experienced difficulty in finding child care that met the quality they desired.38

The increase in teleworking may lead to long-term changes in job flexibility and use of paid child care and, accordingly, to parents’ contributions to child care and family responsibilities within the home. It is also possible, however, that a decline in the use of paid child care and increases in unemployment and teleworking will place greater burden on many Canadians and could increase the gender divide and relationship friction within affected families. Whether or not parents can find quality, affordable, reliable and nearby child care can impact their ability to work in paid employment and their work–life balance,39 as well as the relationships they have with each other and the relationships they have with their children. The impacts of these changes in work patterns and parenting are multifaceted and complex.

On the positive side, many Canadians have reported quality-of-life benefits as a result of working from home or being at home in general during the pandemic. This has particularly been observed in terms of more having more free time and more quality time with immediate family.40 For example, data from Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies (ACS) and the Vanier Institute of the Family in the summer of 2020 revealed that 6 in 10 parents reported that they were talking to their children more often during pandemic than before the lockdown began.41 In addition, more than 4 in 10 (43%) of adults with young children at home said they were relaxing more during the pandemic than they had been before it started.42 An earlier Leger, ACS and the Vanier Institute survey, in April, even reported that 43% of people in married or common-law relationships with children under 18 years of age in the house agreed that they felt closer to their spouse since the start of the pandemic.43

Health: Mental health has been a significant concern during the crisis and persons with a disability may face heightened challenges

For those without strong connections to the economy or sufficient social capital, financial difficulties have often resulted in negative consequences for physical and mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.44 Financial stress resulting from pandemic outcomes have been observed to impact sleep, mental health and mood.45 Impacts on mood and sleep can spread to others in the family and affect their well-being too. According to Dr. David B. Rosen, MD, “Sleep is a family affair… When someone is short-changed, it affects everyone else… [and] has a profound effect on families and family life.”46 Recently, hospitals around the country have reported higher rates of patients being seen for eating disorders.47 , 48

Not surprisingly, the proportion of adults reporting positive mental well-being was lower in studies conducted in 2020 compared with those conducted previous year. Fewer than 6 in 10 (55%) respondents to a Canadian Perspectives Survey in July 2020 reported excellent or very good mental health compared with 7 in 10 (68%) respondents to the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) in 2019.49 Prior to COVID-19, youth aged 15 to 24 were the least likely of any age group to report excellent or very good mental health, and by July 2020 they also reported the largest declines in mental health – a 20 percentage point reduction from 60% in 2019 to 40% in July 2020. Seniors aged 65 and older were the only age group not reporting declines in mental health between the beginning of the pandemic and July 2020.50

Some populations in Canada were observed to report lower mental well-being during the pandemic compared with others. For example, almost 70% of gender-diverse participants responding to a Statistic’s Canada crowdsourcing survey in April and May 2020 reported fair or poor mental health, compared with 25.5% of female participants and 21.2% of male participants.51 The proportion of gender-diverse participants who reported symptoms consistent with moderate/severe generalized anxiety disorder was double (61.8%) that of female participants (29.3%) and triple that of male participants (20.5%). Persons designated as visible minorities were more likely than White people to report both poor mental health (27.8% vs. 22.9%) and symptoms consistent with “moderate” or “severe” generalized anxiety disorder (30.0% vs. 24.2%).52 One report indicated that Indigenous women may have been particularly affected by the challenges of the pandemic, with 48% having reported symptoms consistent with moderate or severe generalized anxiety disorder and 64% having said that their mental health was “somewhat worse” or “much worse” since the start of physical distancing.53

Relationships between changes in mental health and employment status were also observed, with declines between 2019 and March 2020 across employed and unemployed persons alike. The group whose mental health appeared most heavily hit was those who reported being “employed but absent from work due to COVID-19.” However, this group also reported the largest recovery by July 2020, perhaps associated with the impacts of COVID relief programs such as the CERB.54

Persons with long-term health conditions or disabilities who participated in Statistics Canada’s crowdsourcing survey “Living with Long-term Conditions and Disabilities” between June 23 to July 6, 2020 reported declines in both their general health and their mental health as a result of the pandemic.55 Specifically, almost half (48%) of participants with long-term conditions or disabilities reported that their health was “much worse” or “somewhat worse” since before the pandemic and this figure rose to 64% of participants with cognitive difficulties (i.e. learning, remembering, or concentrating) and 60% of those with mental health-related difficulties. Additionally, over half (57%) of participants with long-term conditions or disabilities reported experiencing “much worse” or “somewhat worse” or mental health since the beginning of the pandemic.

According to a February 2021 study of pandemic experiences, more than half of Indigenous participants with a disability or long-term condition reported worsened health across disability types, including seeing, hearing, physical, cognitive, mental health-related or other health challenges or long-term conditions that are expected to last for six months or more.56 The study cited research indicating that those with particular disabilities, where a greater need for in-person care or therapeutic support within their environments is required, may be more adversely impacted by COVID-19 restrictions. Although alternate forms of some services and supports have been provided, prolonged service interruptions without comparable alternatives have left gaps for many, especially among those with specific disability types.

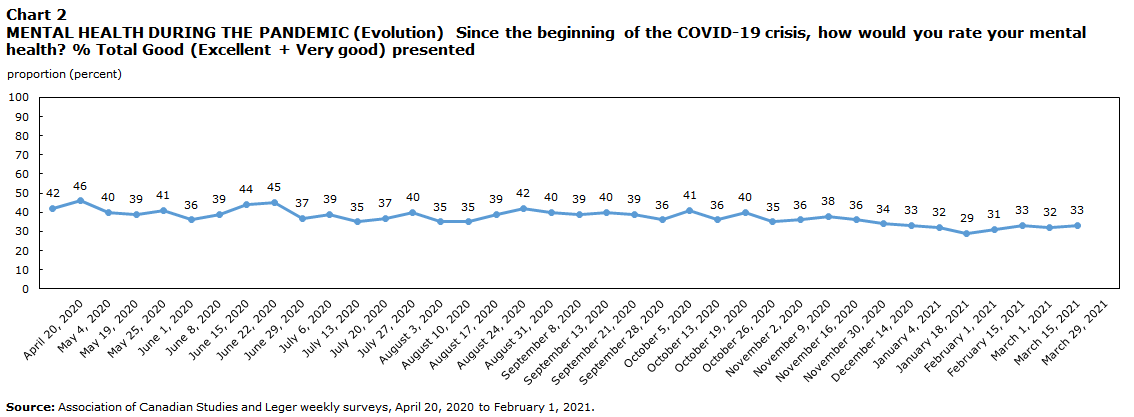

Looking at “within pandemic” mental health only, data from the Association for Canadian Studies and Leger allow for a detailed tracking of mental health during the COVID-19 crisis, offering weekly snapshots of the mental health of Canadians. Over most of the period, it has been difficult to discern a clear trend in positive self-reported mental health, measured to be a response of “excellent” or “very good” to the question “Since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, how would you rate your mental health?” From April 20, 2020 to November 30, 2020, the proportion of respondents giving a positive response was always 35% or higher, and often above 40% (Figure 2). Since December 1, 2020, the proportion reporting positive mental health since the beginning of the pandemic has been consistently below 35% in each week, and has trended downward, reaching 29% by February 1, 2021.57

Environmental quality: Canadians are benefitting from connections to nature closer to home

Studies have found a positive relationship between having a connection to nature and the ability to cope during challenging times. Spending time in natural settings can lead to reduced stress or faster recovery from stress.58 There are numerous other benefits found in both observational and intervention studies, including reduction in diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke and asthma.59

Many Canadians are familiar with the guidelines for physical activity60 that recommend that children get 60 minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity daily and adults 150 minutes weekly. However, fewer know about the recommended 120 minutes per week outdoors.61 Parks and green spaces play an important role in the lives of Canadians, as they have been shown to have positive associations with mental health.62 Fortunately, Canada is lucky to have a high degree of environmental quality, with an abundance of natural resources and green space in many places. In 2017, nearly 9 in 10 (87%) Canadian households reported having a park close by (within a 10-minute journey of their home) and of those households, 85% reported that they had visited it within the previous 12 months. Not surprisingly, households with children (95%) frequented parks more than households without children (82%). Furthermore, overall, people in Canada appeared to be satisfied with their local environment (8.1/10).63

The sales of bikes, kayaks, home exercise equipment, cross-country skis and snowshoes are reported to have increased substantially during the pandemic, and many people could not get their hands on the outdoors equipment they hoped to have.64 During COVID-19, parks provided an opportunity for some to do physical activity, as many gyms and other recreation facilities were closed. They also provided benefits in terms of social connections, as people met for physically distance gatherings outdoors. According to Google’s Community Mobility Report for Canada, activity in Canadian parks was up 117% from baseline levels between mid-May and the end of June 2020.65

In a survey on the role of parks during the pandemic, almost three-quarters (70%) of respondents said that their appreciation for parks and green spaces had increased during COVID-19 and 82% said that parks have become more important to their mental health during the pandemic.66

A Leger survey on trail use reported that 75% of Canadians were using trails for exercise and leisure time in June 2020. A similar study in November 2020 reported that usage of trails was up 50% across all age groups.67 Access to nature was cited as the dominant reason for trail use in Canada. Virtually all (95%) who were using trails said that they were doing so to enhance their mental health as well as for physical exercise and fitness. Nearly 7 out of 10 (69%) said they intended to continue to use trails throughout the winter. A large majority of those with vacations planned for winter 2021 (78%) said they were considering including trails in their winter vacation plans. More than 9 in 10 (91%) strongly agreed that trails are an important source of community recreation, that trails contribute to the economic development of communities (76%) and that trails contribute to building our tourism economy (77%).

At times during the pandemic, national parks and historic sites services were shut down for a period of time as were provincial parks. Play structures were cordoned off and tennis courts, basketball hoops and soccer fields were all off limits. For those who rely on parks, their closure during COVID-19 likely impacted their children’s play and activity. During COVID-19, 16% of Canadians without park access within a 10-minute walk said that they had not used parks at all compared with 3% of those within walking distance of a park.68

Nevertheless, many municipalities around the country are working on creative solutions to give Canadians more opportunities to safely be outdoors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Roads in many places in the country have been shut down in favour of pedestrian and cyclist use and an effort is being made to continue with opportunities for outdoor recreation throughout the winter and spring.69 , 70 Toronto will have more public washrooms open and will maintain an additional 60 kilometres of trails and pathways.71 Other towns and cities, like Prince Albert in Saskatchewan, are calling on their local government to enact creative solutions to allow for more outdoor recreation opportunities.72

Conclusion: Well-being and life satisfaction in Year One of the pandemic

The quality of life and well-being of Canadians and Canadian families have been dramatically impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic over the course of 2020 and in the early months of 2021. The many dimensions across which well-being has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic period have been well documented and the different directions in which quality of life has moved for different segments of the Canadian population has been reported in many studies.

The national experience with respect to quality of life has also been evidenced by the fact that Canadians have, in general, reported a significant decrease in overall life satisfaction. When asked to rate how satisfied they feel with their life as a whole right now on a scale of 0 (dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) the Canadian population scored an average of 8.09 in 2018. However, by June 2020 this figure had declined by 1.38 points to 6.71 – the lowest level of life satisfaction reported over the 17-year period that these data have been recorded.73 Looking at the data another way, the number of Canadians rating their life satisfaction as an 8 or above out of 10 decreased from 72% in 2018 to 40% in June 2020. Youth and immigrants have self-reported the largest declines in life satisfaction since the start of the pandemic.74

Well-being is undoubtedly multidimensional and can be better understood when categorized into domains, further broken down to specific, meaningful indicators. On their own, it can be difficult to imagine how specific environmental factors might relate to mental health, child care use, Internet access or financial resilience, but understanding that there are many drivers and outcomes of well-being and bringing those together using a framework can provide us a more holistic understanding of how people in Canada are faring. Experiences within the COVID-19 pandemic emphasize the multifaceted nature of quality of life, and studies such as this one suggest that a full accounting leads to a better understanding of the impact that COVID-19 has had on Canadians.

One way of bringing together the findings of this paper is through reflecting on the importance of connections in people’s lives, and connections and relationships do appear to be the common denominator of the well-being dimensions examined in this article. These are connections between people and employment, technology, family, the environment and mental health. Moreover, each domain impacts and is impacted by the others.

Having a strong connection to the labour force might be reflected by various factors, including predictable and adequate employment and a high degree of financial resilience, which can increase financial well-being. Financial well-being can also be influenced by access to technology that allows for the creation of resumés, applying for jobs, virtual work from home or strengthened contacts with others. Technology has allowed Canadians to connect through video calls to each other and has facilitated participation in social, education and work environments.

Those who have access to quality, affordable child care may be more likely to have higher disposable incomes and may not have their time and energy spread as thin as those attempting to juggle care duties alongside their other responsibilities. Disposable income and time can in turn allow for the pursuit of leisure activities, including outdoor activities, which impact both physical and mental well-being. Canadians who take time to get outside, chat with their neighbours and visit parks may have better mental and physical health leading to improved resilience. For those who are saving time without a commute and saving on dining-out bills, they may now spend more time with family and friends, eating healthier home-cooked meals at home.

In this paper, results were shown for only about half of the dimensions of quality of life presented in the OECD Well-being Framework, only a few variables were included and only limited evidence on the diversity of outcomes in these variables was presented. This underscores both the importance and the challenge of having and using a well-being lens and maintaining a meaningful perspective quality of life – a large set of variables needs to be collected, followed and disaggregated to fully describe changes in well-being over time and to understand the drivers of change.

Canadians’ Well-being in Year One of the COVID-19 Pandemic

by Sarah Charnock, Andrew Heisz, and Jennifer Kaddatz , Statistics Canada, Nora Spinks and Russell Mann, The Vanier Institute of the Family

Recent Comments